Advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) instrumentation have dramatically increased the pace of data acquisition. Modern microscopes can now deliver multiple datasets suitable for high-resolution structures within a single 24-hour microscope session. However, as data acquisition has accelerated, the bottleneck has shifted downstream, where data processing now increasingly limits throughput.

Public cryo-EM repositories such as EMPIAR provide a unique opportunity to systematically evaluate and refine automated structure-determination workflows. At CryoCloud, we initiated the EMPEROR project to take advantage of this. The EMPEROR project uses the large number of previously deposited datasets to build and stress-test CryoCloud’s end-to-end automation across a wide range of targets, acquisition parameters, and data quality. By reprocessing these datasets at scale, we gain a detailed overview of where automation excels and where targeted improvements are required, allowing us to iteratively refine our workflows toward a more generalised pipeline that is applicable to most cryo-EM targets.

In this blog, we highlight an example from a recent unsupervised workflow benchmark: the gastric proton pump bound to the potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB) revaprazan (EMPIAR-11057).

A clinically relevant membrane protein

The gastric proton pump (H⁺/K⁺-ATPase) is a membrane protein responsible for acid secretion in the stomach and is a clinically relevant drug target for the treatment of acid-related disorders. Potassium-competitive acid blockers (P-CABs) inhibit the pump by competing with potassium ions at the binding site of the ATPase. P-CABs have attracted interest due to their rapid onset and reversible mode of action when compared with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

The dataset discussed here, EMPIAR-11057, captures the proton pump in complex with the P-CAB revaprazan. In the published structure, revaprazan is clearly visible and adopts a conformation in which its tetrahydroisoquinoline moiety inserts deeply into the transport conduit. The biological relevance of this target and the clear ligand density in the published map make it an ideal test-case for assessing the quality of our fully automated processing pipeline.

Fully automated processing with CryoCloud

We reprocessed EMPIAR-11057 using CryoCloud’s end-to-end automated cryo-EM pipeline, starting from raw movie files and proceeding to a final 3D reconstruction. The workflow ran without manual intervention or iterative parameter tuning. All steps were executed on CryoCloud’s cloud-native infrastructure, which has been purpose-built to optimise job scheduling, stability, and throughput for cryo-EM workloads.

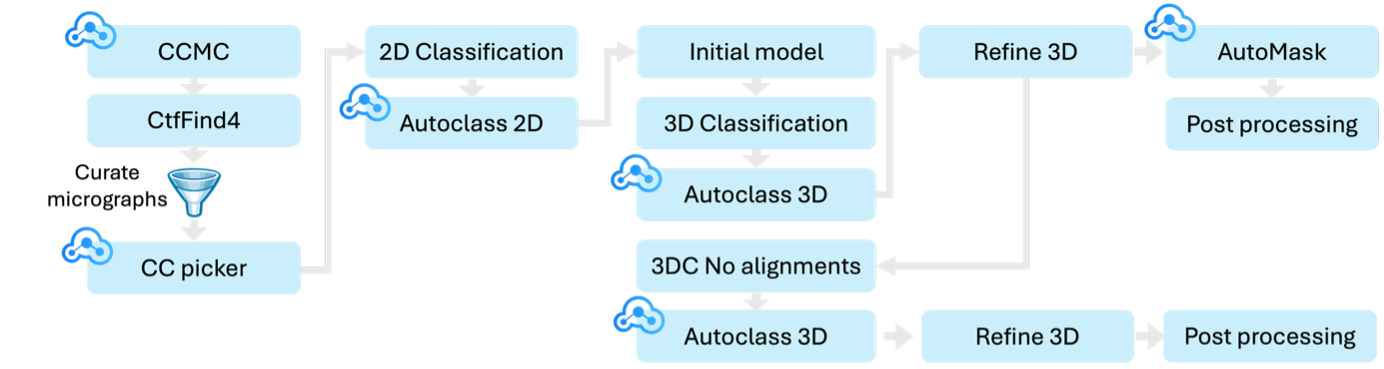

Figure 1. Automated workflow applied to EMPIAR-11057: Steps marked with the CryoCloud logo use CryoCloud's own algorithms: CryoCloud motion correction (CCMC), CryoCloud Picker (CC picker), AutoClass2D, AutoClass3D and AutoMask. Micrographs were curated based on estimated resolution (6 Å cutoff) and ice thickness.

Figure 1. Automated workflow applied to EMPIAR-11057: Steps marked with the CryoCloud logo use CryoCloud's own algorithms: CryoCloud motion correction (CCMC), CryoCloud Picker (CC picker), AutoClass2D, AutoClass3D and AutoMask. Micrographs were curated based on estimated resolution (6 Å cutoff) and ice thickness.

Results: quality and speed

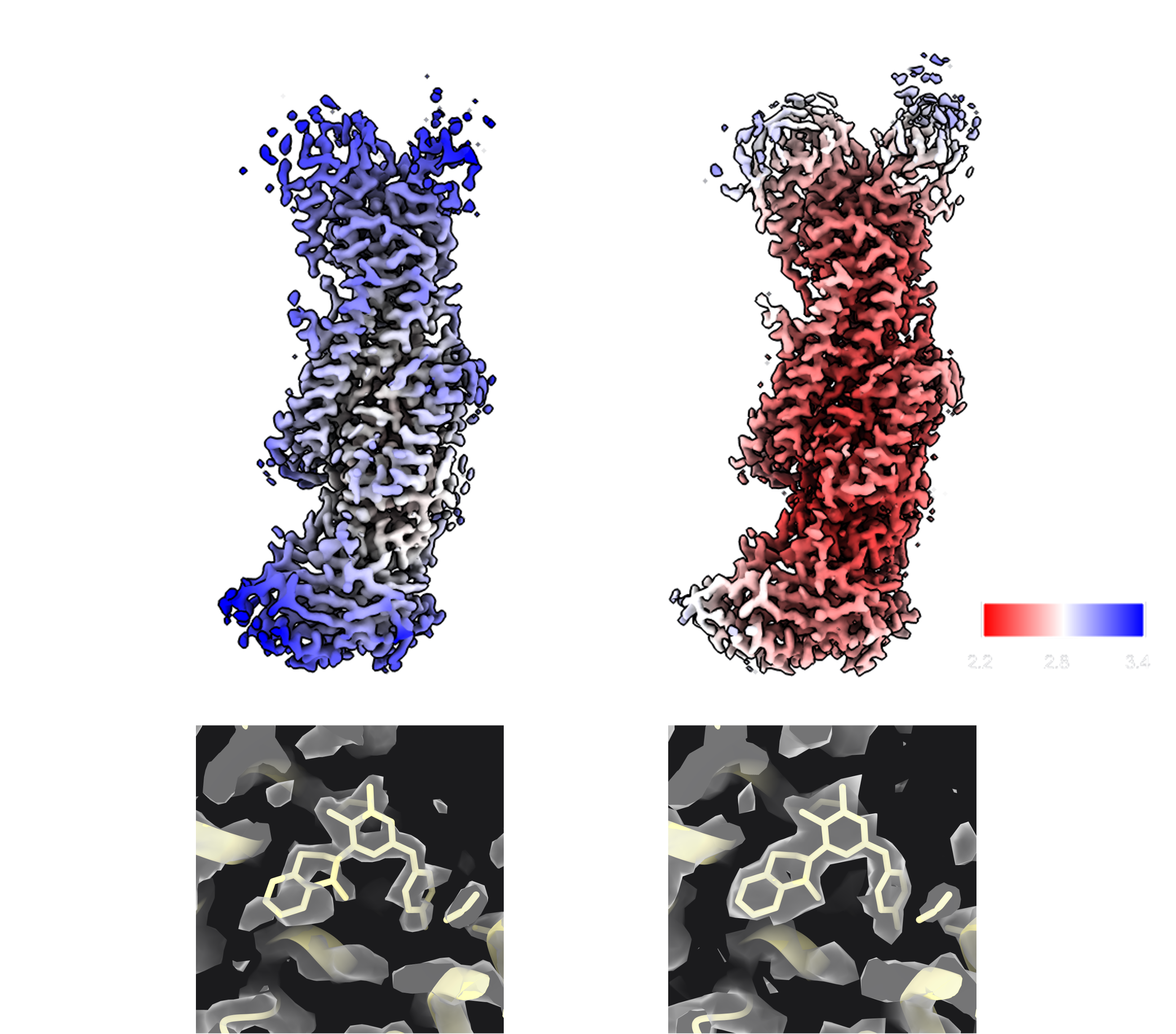

The automated workflow produced a final reconstruction at 2.6 Å resolution in a total compute time of 43.5 hours, improving slightly on the 2.8 Å resolution reported in the original publication. The final map clearly resolves the bound revaprazan molecule, including density for the tetrahydroisoquinoline moiety within the transport conduit. Notably, the original workflow did not include CTF refinement or polishing, both of which could be added without compromising automation. A subsequent CTF refinement routine on the same particle stack improved the resolution to 2.4 Å.

Figure 2. Comparison of outputs from deposited maps and maps generated during automated re-processing. A,B) Map filtered and coloured by local resolution, generated from deposited halfmaps (EMDB-32299) (left) and map filtered and coloured by local resolution generated using halfmaps from final re-processed refinement (right). Colour key for local resolution is shown bottom right. C,D) Density for revaprazan in the sharpened deposited map (left) and the re-processed map (right).

Figure 2. Comparison of outputs from deposited maps and maps generated during automated re-processing. A,B) Map filtered and coloured by local resolution, generated from deposited halfmaps (EMDB-32299) (left) and map filtered and coloured by local resolution generated using halfmaps from final re-processed refinement (right). Colour key for local resolution is shown bottom right. C,D) Density for revaprazan in the sharpened deposited map (left) and the re-processed map (right).

This result demonstrates that automated pipelines can deliver high-quality maps without human supervision and, crucially, on a time-scale that facilitates high-throughput applications e.g. batch processing of screening datasets for identification of optimal sample/grid conditions, or epitope mapping experiments. Importantly, automated pipelines also promote efficient use of computing resources by avoiding manual iterations, reducing the cost per structure in the cloud.

In-house algorithms enable efficient automation:

Pre-processing

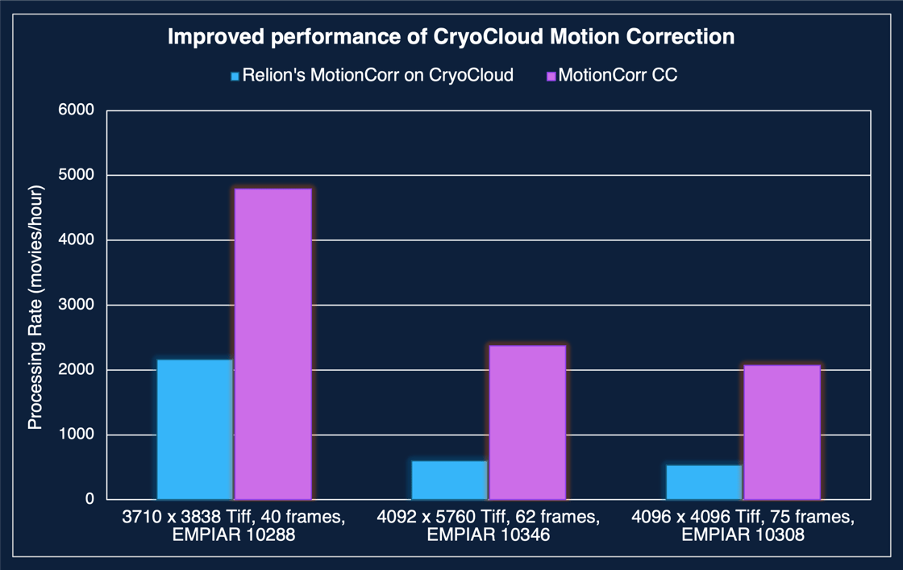

Our patch-based motion correction algorithm (CryoCloud MotionCorr) processed the raw data at a rate of 3,242 movies per hour, ensuring that motion correction did not become a bottleneck in the automated workflow.

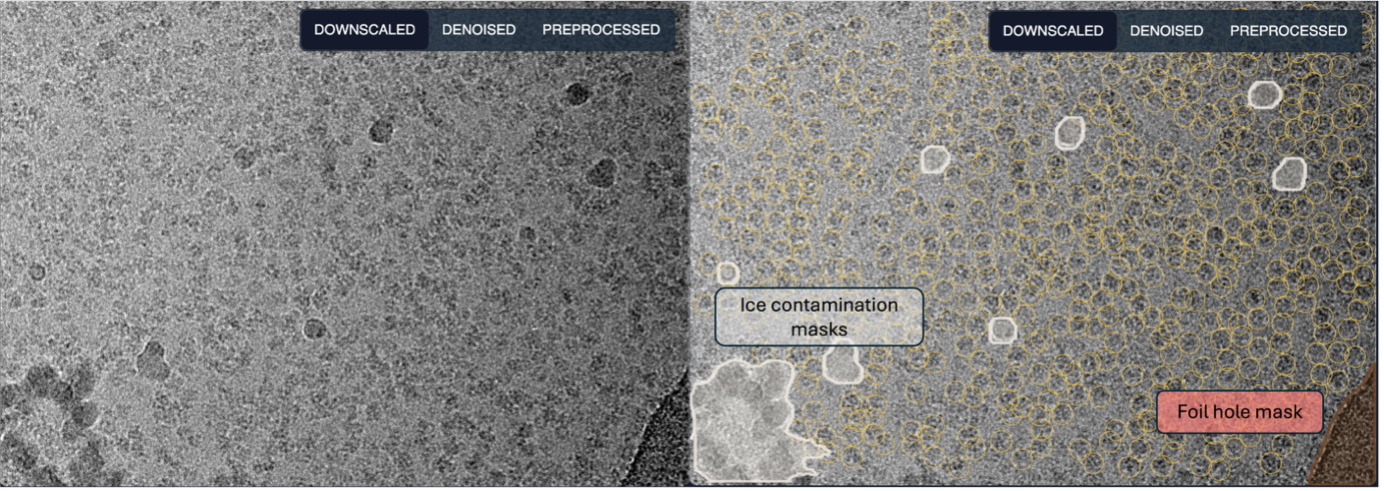

The CryoCloud picker leverages advanced ML models to quickly and accurately pick particle coordinates whilst identifying and masking regions of ice contamination and foil holes in the image.

Figure 3. Example output from CryoCloud's ML picker. Unpicked micrograph (left) shown alongside picked and masked micrograph (right). Particle coordinates are indicated by yellow rings. Masks for ice contamination are shown in white, while the foil hole mask is shown in red.

Figure 3. Example output from CryoCloud's ML picker. Unpicked micrograph (left) shown alongside picked and masked micrograph (right). Particle coordinates are indicated by yellow rings. Masks for ice contamination are shown in white, while the foil hole mask is shown in red.

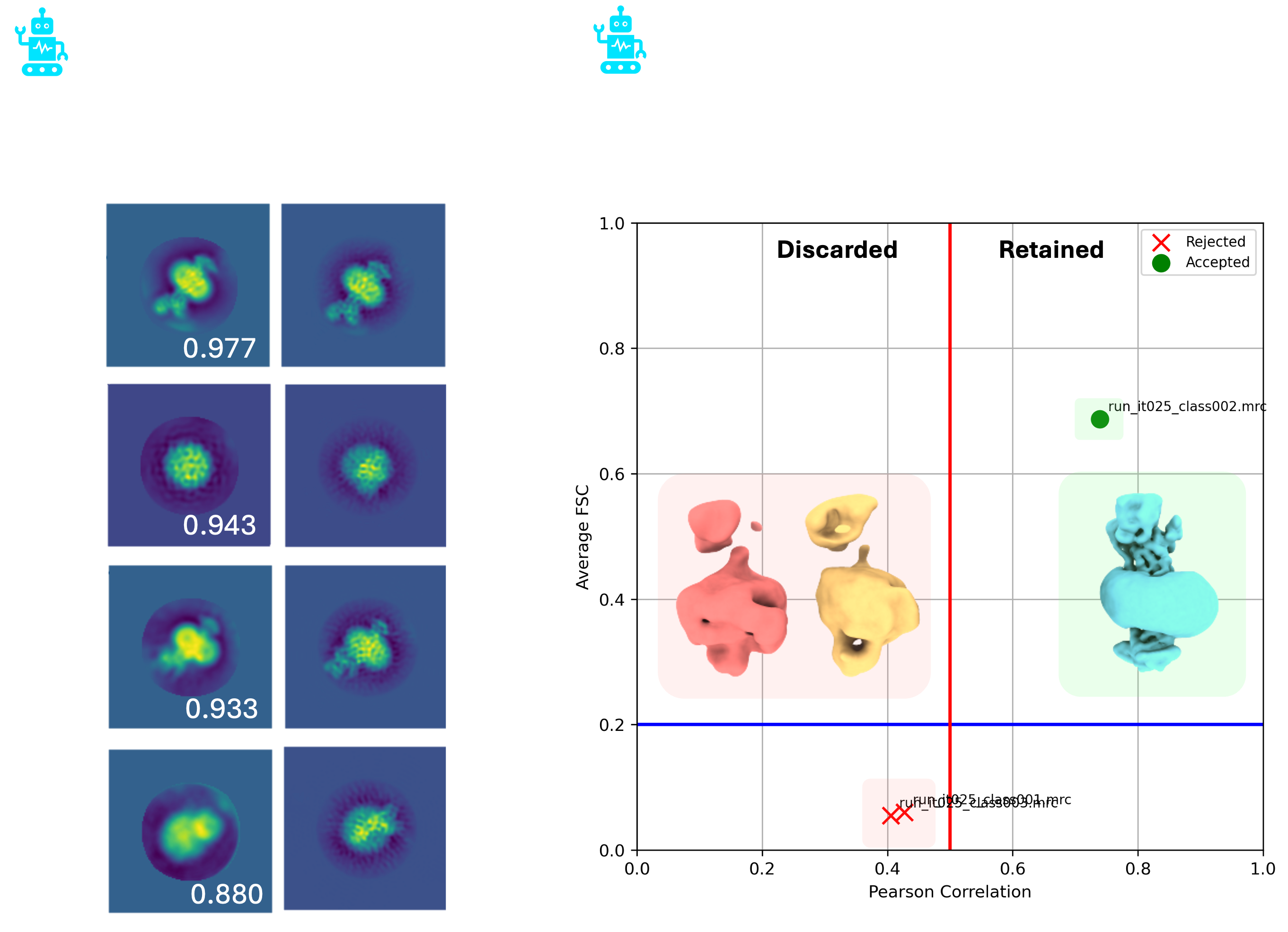

Autoclass2D and AutoClass3D jobs replace the manual selection of classes. Both algorithms use a reference map to identify classes of interest. For 2D, the reference is projected at a range of viewing angles which are then cross correlated with the experimental 2D class averages. The resulting Pearson correlation coefficients are then used as a selection criterion where classes scoring above a pre-defined threshold are taken forward. A similar cross-correlation approach is used in 3D.

Where an autoclass3D job follows a classification job in which no alignment is performed (particle sorting), the selection criterion is no longer based on cross-correlation but rather resolution, with particles belonging to the highest resolution class taken forwards.

Figure 3. Example outputs from AutoClass2D and AutoClass3D. Representative 2D class averages with their matched reference projections (left). Cross-correlation scores are shown for each pair. 3D class averages that were discared and retained by AutoClass3D overlaid with a plot of their Pearson correlation against average FSC (right). The Pearson correlation threshold for retaining a class is indicated by the vertical red line.

Figure 3. Example outputs from AutoClass2D and AutoClass3D. Representative 2D class averages with their matched reference projections (left). Cross-correlation scores are shown for each pair. 3D class averages that were discared and retained by AutoClass3D overlaid with a plot of their Pearson correlation against average FSC (right). The Pearson correlation threshold for retaining a class is indicated by the vertical red line.

It is important to note that 3D refinement jobs utilise a shape mask (not spherical) by default. The shape masks are automatically generated as part of the workflow by CryoCloud’s AutoMask job. This same tool allows mask generation for use in post-processing operations, removing manual mask creation steps and permitting end-to-end automation.

Automation facilitates throughput and accessibility

Fully automated cryo-EM processing is not about removing expert oversight, but about eliminating manual steps that limit scalability, consistency, and throughput. By reducing user-dependent decision making while preserving full traceability, automation enables cryo-EM analysis to scale beyond individual datasets and expert users. The reprocessing of EMPIAR-11057 demonstrates the impressive capability of automated workflows, delivering a map of a clinically relevant membrane protein with clear ligand density at a resolution better than originally published, and completed in under two days of compute time without manual intervention.

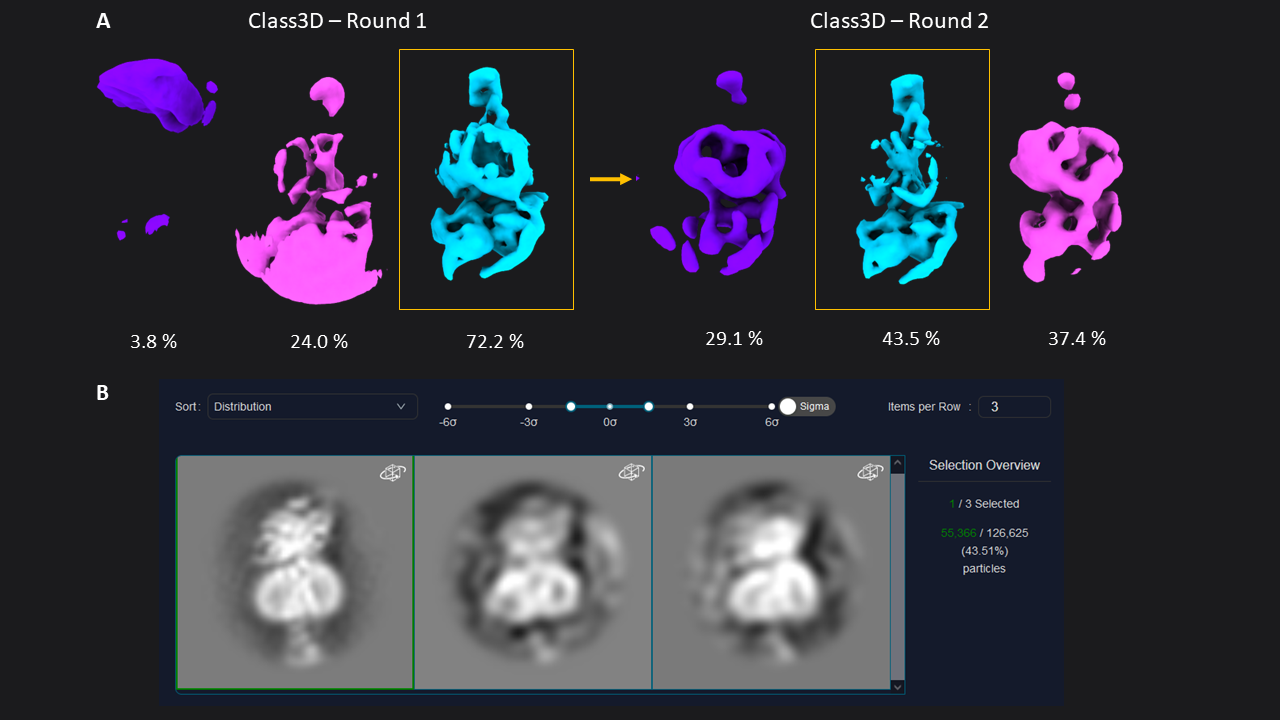

Figure 1: 3D classification of particles and class selection in CryoCloud. A) The set of extracted particles (n= 174,928; box size = 70; pixel size = 3.03 Å) was subjected to two rounds of 3D classification. The well-defined class from the first round was used as input for the second round, resulting in a well-defined class average from a subset of 31% of the total picked particles (selected classes in yellow boxes). B) 3D Class selection panel in CryoCloud - one of several interactive jobs with a custom developed interface, providing sorting of classes and contrast adjustment, and displaying class metadata and total number of picked particles in this case.

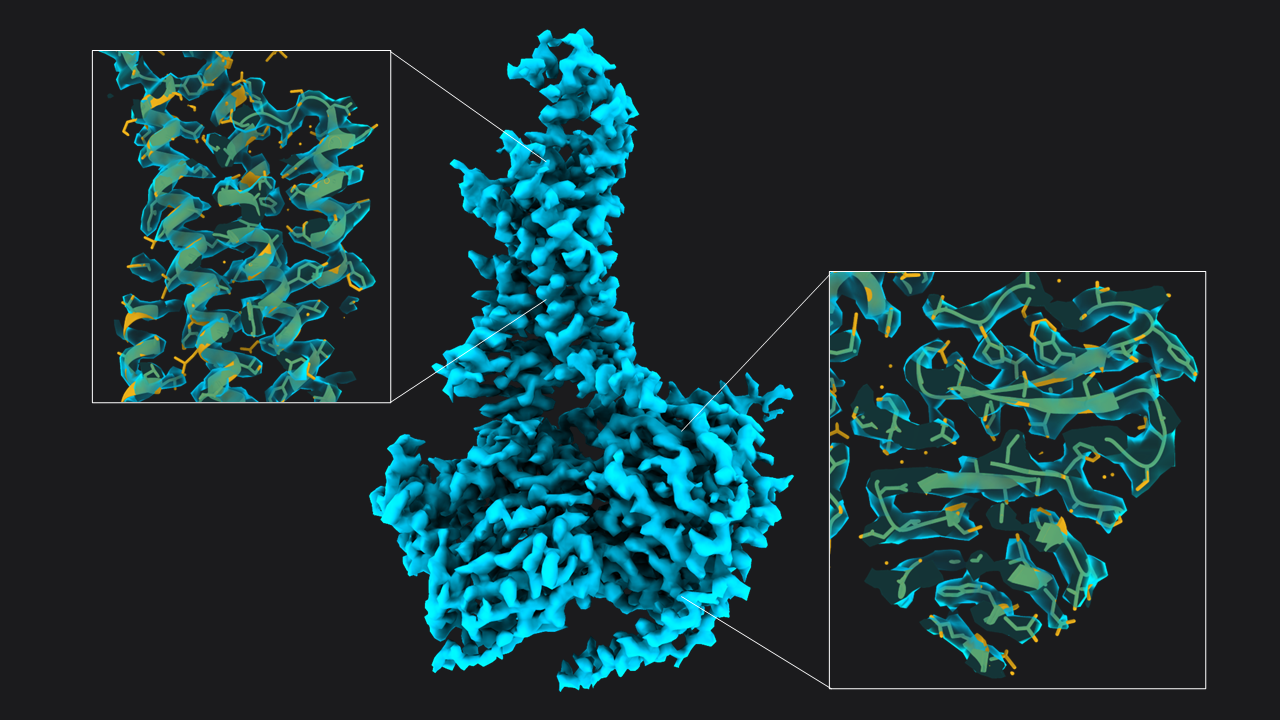

Figure 1: 3D classification of particles and class selection in CryoCloud. A) The set of extracted particles (n= 174,928; box size = 70; pixel size = 3.03 Å) was subjected to two rounds of 3D classification. The well-defined class from the first round was used as input for the second round, resulting in a well-defined class average from a subset of 31% of the total picked particles (selected classes in yellow boxes). B) 3D Class selection panel in CryoCloud - one of several interactive jobs with a custom developed interface, providing sorting of classes and contrast adjustment, and displaying class metadata and total number of picked particles in this case. Figure 2: Structure of GLP-1-R bound to GLP-1 at 3.54 Å resolution. Map obtained from ~55,366 particles (pixel size = 1.33 Å, box = 160 pixels) after two rounds of 3D refinement and post-processing. Boxes show slices through the map overlapped with the atomic model (

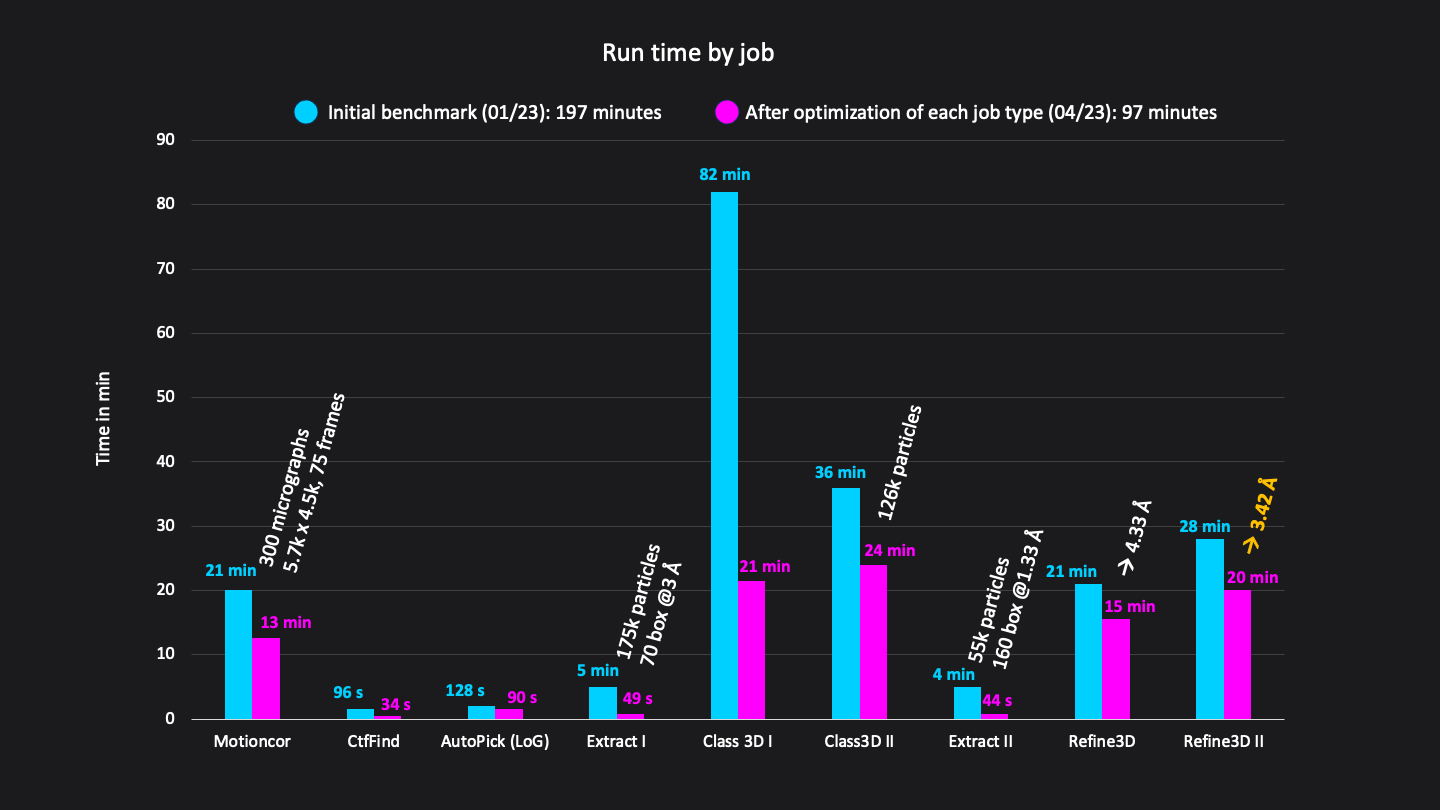

Figure 2: Structure of GLP-1-R bound to GLP-1 at 3.54 Å resolution. Map obtained from ~55,366 particles (pixel size = 1.33 Å, box = 160 pixels) after two rounds of 3D refinement and post-processing. Boxes show slices through the map overlapped with the atomic model ( Figure 3: Runtimes of each job in minutes. Excluding short jobs like selection, mask creation and postprocessing the whole analysis workflow consisted of 9 jobs and was done in a total run time of 192 minutes on CryoCloud.

Figure 3: Runtimes of each job in minutes. Excluding short jobs like selection, mask creation and postprocessing the whole analysis workflow consisted of 9 jobs and was done in a total run time of 192 minutes on CryoCloud.